Two Funds for Life, Pre & Post Retirement

By Chris Pedersen

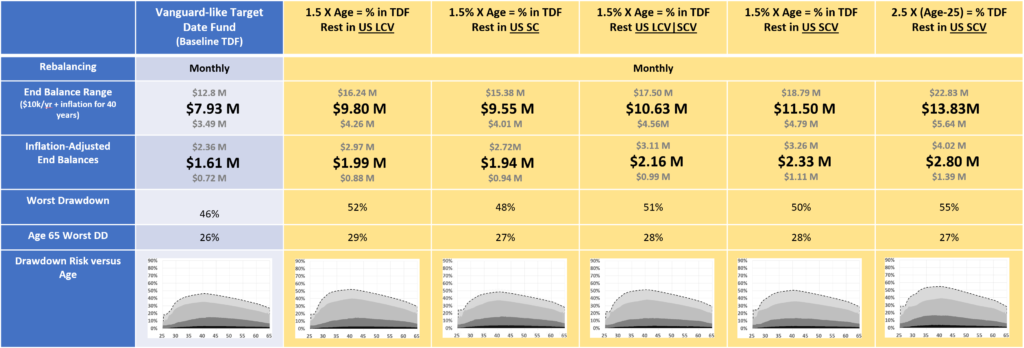

In 2018, Paul and I introduced a new investment approach we called two funds for life. The goal was to come up with a simple approach that would help young investors do better. It started with the observation that target-date funds (TDFs) are wildly popular, well-diversified, cost-effective investments that prudently reduce risk for investors as they approach retirement. What we found, using the industry-leading Vanguard Target Retirement funds as a model, was that they are overly conservative during a typical investor’s early years since they hold bonds, and have no meaningful representation of the small and value asset classes. One reason young investors can take more risk is that regular contributions & purchases dramatically reduce the downside volatility an investor experiences if they start, as most do, with a small balance. To offset this over-conservatism, we proposed a simple approach: multiply age by 1.5 and use that as a percentage to invest in the appropriate TDF and put the rest into an all-equity fund, ideally tilted towards small and value assets. In backtesting, this approach outperformed a pure target date fund approach significantly in more than 99% of the 40-year periods tested, and only increased portfolio downside risk by 2% to 6%. Here’s the summary data from that study (please see the original article for a full explanation of the details).

The approach also triggered many unanswered questions, mostly related to applying a two-fund strategy at or in retirement. In this article, we’ll fill in the gaps for people who plan to retire early, people just starting retirement, and people already in retirement.

How do I apply Two Funds for Life if I want to retire early?

With the growing popularity of the FIRE (Financial Independence Retire Early) movement, more and more people are interested in retiring early. More importantly, they are doing what’s needed to make early retirement possible. They are living frugally and saving aggressively. Assuming that results in a nest egg large enough to enable retiring much younger, how would you apply the Two Funds for Life strategy which was originally built on an assumption of retiring around age 65?

The answer is relatively simple, and in fact, can be used whether you plan to retire early or not. Instead of using 1.5 times your age to determine the percentage you would invest in the target-date fund, you turn it around and use 1.5 times the years left to retirement to determine the amount you would invest in the second fund. So, if you are 30 years old, and plan to save aggressively to retire at age 50, you would be 20 years from retirement, and 1.5 X 20 = 30, so you’d invest 30% in small-cap value (or other asset class of your choice) and 70% in the TDF.

The obvious follow-on question is how does that change the numbers? The answer is it depends. Because there are so many variations on the early retirement approach, it’s not practical to summarize them in a single table. It would probably take a series of tables like the one above where each table considered different savings rates and years to retirement. If we can’t answer all of those questions, maybe we can answer a more important question. Will it still help? As always, there are no guarantees, but the same principles that make this strategy work for age 65 retirees can help early retirees. The Two Funds for Life strategy will still mitigate the overly conservative approach of target-date funds in the early years, potentially increase returns with only slight increases in drawdown risk, and ramp that risk down approaching retirement.

How do I apply Two Funds for Life if I’m transitioning to or already in retirement?

If you’re at or in retirement and hear about this strategy, it’s easy to feel left out. If age times 1.5 equals 100 or more, does that mean I should just be 100% in the target date fund at age 67?

The answer is “it depends.” Primarily, it depends on whether you’ve saved enough. One way to know whether you have or not is to calculate how much or your nest egg you’ll need to spend every year to meet your expenses. This is called your withdrawal rate.

Say you’ve got $1M saved and invested and can live on $50k per year. That would be a 5% ($50,000 / $1,000,000) withdrawal rate. But let’s say you also get $10k per year in social security and pension benefits Now, you only need to spend $40k from your nest egg or a lower 4% per year withdrawal rate.

There’s been a lot of research done to suggest a fixed 4% withdrawal rate is a good target. Fixed means you calculate how much you will withdraw at retirement, then increase the dollar amount by inflation (not your investment gains or losses) every year until you die. Keep in mind that the 4% withdrawal rate was tested for a normal retirement age. If you plan to retire much earlier than age 65, you may need to have a lower withdrawal rate to make your money last.

So, if you’re of normal retirement age, and need more than a 4% withdrawal rate, we could say you’ve under saved by a bit. On the other hand, if you need less than that, then we could say you’ve over saved. And right around the 4% rate, we’d call just right.

If you’ve under saved, don’t despair, but do see a financial planner.

There will be a path forward, but it’s more likely to require some creativity and less likely to fit a boiler-plate template answer. It may involve working more, lowering expenses, increasing savings rates, changing investment portfolios or other approaches. A good financial planner should be able to walk you through the options and help you see a way forward without it costing you an arm and a leg.

If you’ve saved just the right amount, congratulations! You’re a rare breed!

The Two Funds For Life approach is fairly easy to extend into retirement for someone who has saved just enough because that’s pretty much what the target date fund managers plan for. Sticking with a 100% allocation to the target date fund in retirement is simple and prudent. It may err on the conservative side, but this may be what’s needed by retirees transitioning from regular paychecks to living off their investments. Once retirees are comfortable living off of their investments, it may make sense to shift back to a two-fund approach if they can stick with it through a little more volatility. Testing with the Financial Goals Monte Carlo simulation tool at www.portfoliovisualizer.com suggests allocating 10-20% away from a Vanguard-like target date fund allocation towards low-cost, all equity index funds could increase returns significantly and reduce the likelihood of running out of money.

If you’ve saved more than enough, wow! You’ve got options.

The simple way to think about your options is to think that you have two buckets. The first bucket is the part of your portfolio that you need to live on in retirement. This is the portion required to enable a 4% withdrawal rate. So, if you need to withdraw $50k per year to meet expenses, $1.25M ($50k / 4% or 25 X $50k) of your investments would be invested as your retirement portfolio. Investing this portion in a target date fund is again simple and prudent. Whatever you have beyond that can be invested more aggressively since it will likely be passed on to children and charities when you die. If you want to stick with a two fund solution, you could invest the “extra” in any one of the second fund choices modeled in the Two Fund for Life analysis. If you want more diversification, you could choose something like a worldwide small-cap value plus emerging markets, all value, or Ultimate Buy and Hold portfolio.

Setting expectations & sticking to the plan

Good investing takes many of the same qualities required for a good marriage. It’s important to remember what drove your choice in the first place and not always be looking for something better.

If you’re in the accrual phase, look at the table at the beginning of this article, and read the article it came from. That will give you a pretty good idea of what to expect. You won’t see big drawdowns in the early years, but they’ll increase toward the middle of your career and then come down a bit. If the market’s down, and you’re down a bit more than the market, that’s OK. You chose a strategy that does that because it’s likely to lead to a better outcome in the end. Don’t panic. Stay the course.

If you’re nearing retirement or in retirement, I have good news for you. There’s a tool to help paint a picture of the range of things you’re likely to experience. The tool is the Financial Goals page of the Portfolio Visualizer website. Here’s a link to an example: https://bit.ly/2mr1Wqg

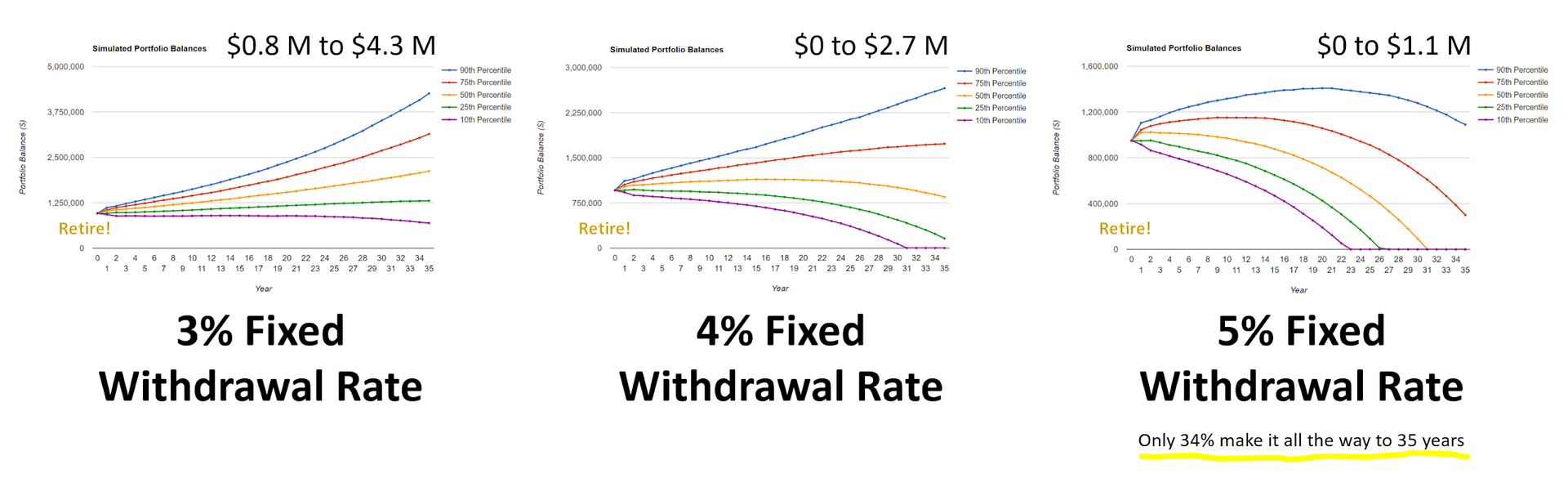

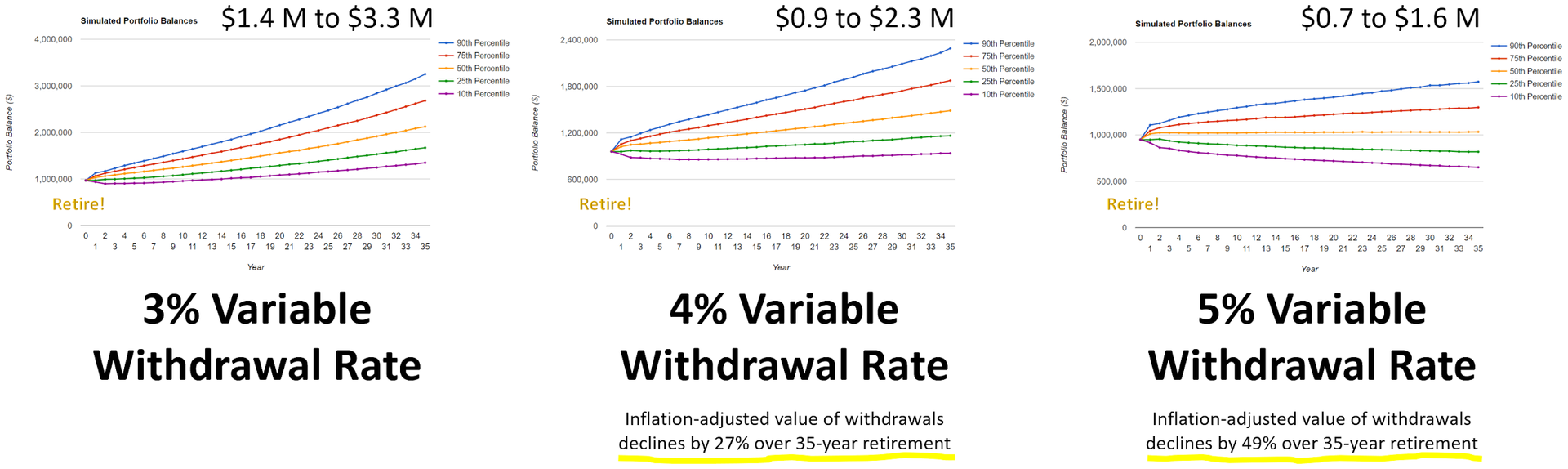

And here are some example scenarios for what might happen to a $1M nest egg over 35 years of three to five percent fixed withdrawal rates using a Vanguard-like target date fund allocation.

Follow the link if you want to see all the details in these kinds of graphs. For our discussion, the general shape is enough. What you see are a series of lines representing simulated portfolio balances over time. The analysis models the changing Vanguard-like target retirement fund asset allocations and withdrawals during retirement. The different lines describe very bad luck (bottom line, 10th percentile), bad luck (25th percentile), average luck (50th percentile), good luck (75th percentile, and very good luck (top line, 90th percentile), and can be useful to help set expectations about how much you might expect your portfolio to go up and down over time. Perhaps the most striking thing is that some of the lines don’t go all the way across the chart. It’s easy to see from the 5% fixed withdrawal rate chart why 5% is not a recommended safe withdrawal rate since only 34% of the simulations still had money at the end of the 35 years.

Here’s the same kind of analysis for variable withdrawal rates. https://bit.ly/2mpTkQK

Since the withdrawal is always a percentage of the balance, there’s no way to run out of money, but you could see smaller and smaller withdrawals over time if you’re taking out too much. That’s what we see for both the 4% and 5% variable withdrawal rates using the Vanguard target retirement account asset allocations. By the end of the 35-year simulations, the 4% variable withdrawal rate experiences an inflation-adjusted decline of 27% in spending power of the withdrawals, and the 5% variable withdrawal rate sees a decline of almost 50%.

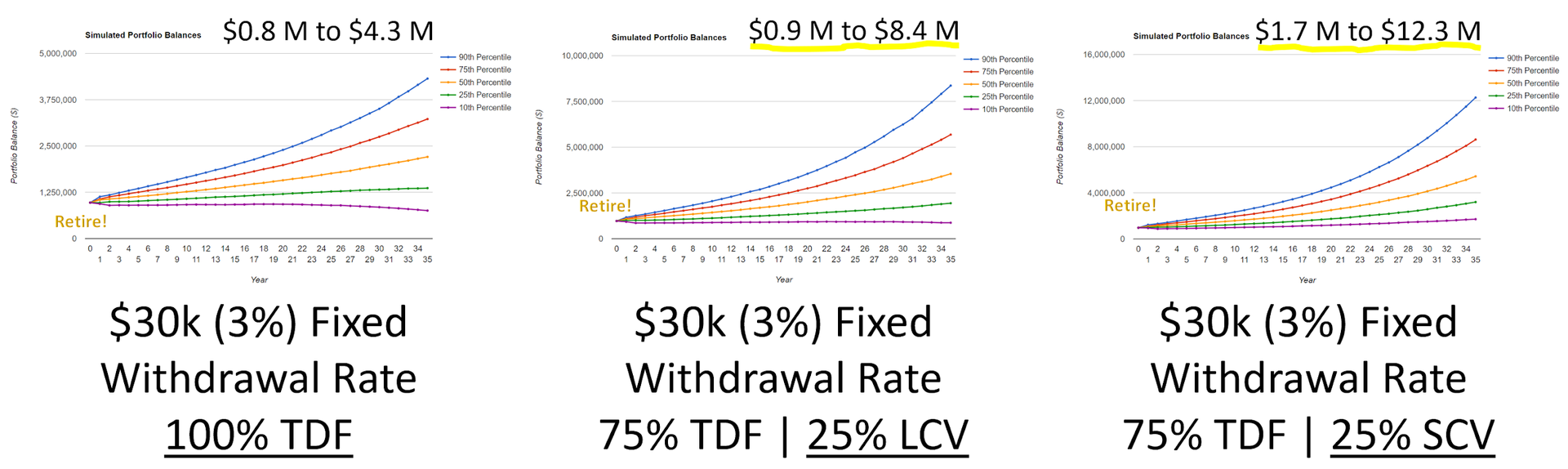

You may be wondering if we can use the same tool to model the two fund strategies an over-saver might use in retirement. The answer is “yes!” It takes a little bit of calculation to figure out the portfolio allocations, but here are three scenarios which all start with $1M and a $30,000 fixed (increasing w/ inflation) withdrawal rate. Since we’re frugal and can live on 3% or $30k (which is 4% of $750k) per year withdrawals, but have $1M saved, that means we have $250k ($1M minus $750k) “extra” which we can invest in a second fund. For comparison, the first chart assumes everything is in the target-date fund. The second assumes the “extra” $250k is in a large-cap value fund, and the third assumes the “extra” $250k is in a small-cap value fund.

I hope this is getting you at least a little bit excited. By investing the “extra” or over-saved portion of our savings in either large-cap value or small-cap value, history suggests we could end up with two to three times as much money to pass on to our heirs. Perhaps just as interesting is the fact that the lowest 10th percentile balances, the “bad luck scenarios” are actually better with the second fund added. Of course, we can’t buy the past, but if the future looks even a little like the past, it will likely help.

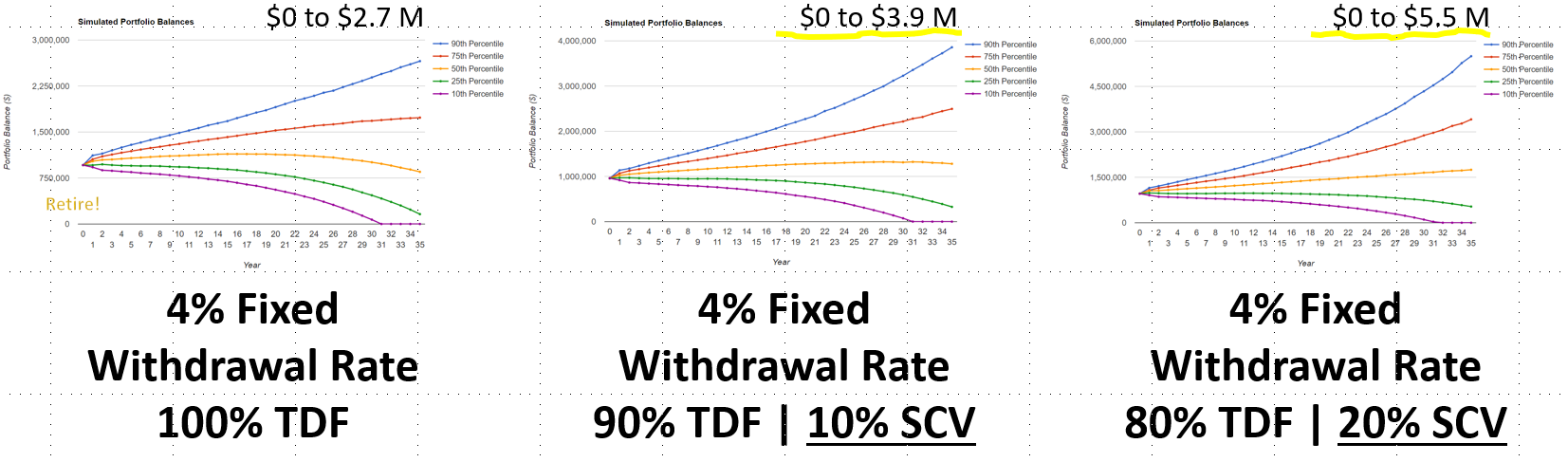

Finally, let’s look at how this might help people who’ve saved just enough. Although the target date fund is prudent, would allocating some part of the portfolio to small-cap value help or hurt? We can run those simulations at Portfolio Visualizer too. Here they are.

It shows that even for those without “extra,” a small allocation of 10-20% could improve their likely outcomes by millions of dollars, and do it without increasing the likelihood of running out of money in retirement.

Conclusions

The Two Fund for Life strategy is fairly easy to apply in a wide range of circumstances including early retirement, nearing retirement and in retirement. The places where a second fund helps the most are early in an investor’s life where target-date funds tend to be overly conservative, and late in an investor’s life if they’ve over saved and can take on more risk with assets that are earmarked for the next generation. In both cases, augmenting a target-date fund with a second all equity fund seems likely to significantly improve long-term returns with only small increases in drawdown risks. Though the approach seems simplistic, it provides worldwide diversification across thousands of companies, with dynamic age-related portfolio risk management, and does it all at a very low cost.

The Merriman Financial Education Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) organization founded in 2012.

All donations are used to support our work. Deductions are permissible to the extent of the law.

Contact us at info@paulmerriman.com

All information on this site is provided free of charge (with the exception of books for sale) and is funded in full by The Merriman Financial Education Foundation.

Anyone wishing to use this educational information in web-based or printed materials are welcome to do so with the following attribution and link:

“This information freely provided courtesy of PaulMerriman.com.” We would also appreciate a copy and link of where it has been published via email.

All Rights Reserved